Integrating Rust in a C codebase

15 Apr 2023As a new software developer, I’m constantly investigating how to strengthen my skills and keep up with industry trends. Recently, I have read that Linux, has added support for developing with Rust aiming to attract younger developers to the project. So, I decided to challenge myself and see if I could integrate Rust into a C code base. In this article, I’ll share my experience of exploring the intersection between these two languages and the lessons I learned along this short of the way.

The beginning

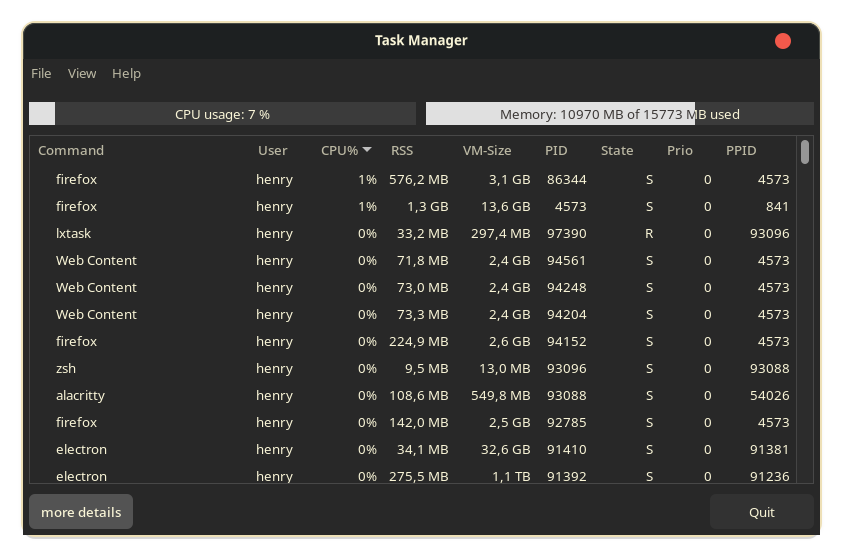

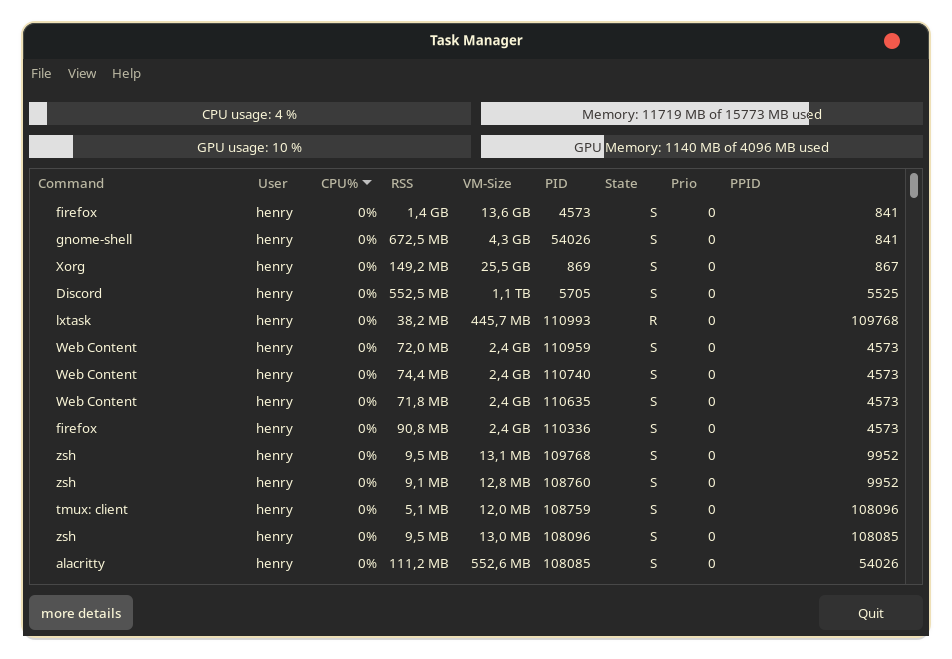

The main idea was to get the simplest and functional project written in C that matched with my skills to add the smallest feature I could, that, in this case, was the bar’s monitor for GPU in the LXTasks.

I, like many other developers, had a contact with C in college or when learning programming. Due to that, the knowledge I have about C is more generic and less practical, which made me concerned about how complex the code that I would decide should be. Thinking this way, LXTasks fit well with my requirements.

So, the first step was trying to add the smallest code I could: a simple function that returns a number. To achieve that, as I read, I need a head file with the function signature to be included and an object file with the implementation to be linked.

A header file contains C declarations and macro definitions that can be shared between multiple source files. There are two types of header files: system header files and “user” header files. System header files provide the interfaces to parts of the operating system, and they are used to provide the definitions and declarations needed to invoke system calls and libraries. User header files contain declarations for interfaces between the source files of your program.

#ifndef __EXTERNAL_H__

#define __EXTERNAL_H__

int get_int()

#endif

Here is the HTML content converted to Markdown:

In my case, It is a “user” header file containing the necessary declarations that the object file compiled from Rust should meet for the linking process to be successful.

Object file

According to Object File article, “An object file is a computer file containing object code, that is, machine code output of an assembler or compiler. The object code is usually relocatable, and not usually directly executable. There are various formats for object files, and the same machine code can be packaged in different object file formats. An object file may also work like a shared library. […] A linker is then used to combine the object code into one executable program or library, pulling in precompiled system libraries as needed.”

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn get_int() -> std::ffi::c_int {

return 1;

}

With the code ready for the first test, built the project with the object file

created from Rust. To that, I’ve written a simple and small Shell script to

compile, and link everything to produce the final executable binary. This script

has used the rustc, Rust

compiler, to generate the object file called debug.o inside src/, and the

GCC, GNU Compiler Collection, to all objects files from

C.

All objects files compiled, I’ve to link everything together and build the final

lxtask Elf file itself.

#!/bin/env sh

# rm src/debug.o

rustc src/debug.rs --crate-type staticlib --emit obj -o src/debug.o

if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

echo "Failed to compile external.rs"

exit 1

fi

for i in src/*.c; do

rm ${i%.c}.o

gcc -c $i -o ${i%.c}.o -DVERSION=1 -pthread -I/usr/include/gtk-2.0 -I/usr/lib/gtk-2.0/include -I/usr/include/pango-1.0 -I/usr/include/glib-2.0 -I/usr/lib/glib-2.0/include -I/usr/include/sysprof-4 -I/usr/include/harfbuzz -I/usr/include/freetype2 -I/usr/include/libpng16 -I/usr/include/libmount -I/usr/include/blkid -I/usr/include/fribidi -I/usr/include/cairo -I/usr/include/pixman-1 -I/usr/include/gdk-pixbuf-2.0 -I/usr/include/atk-1.0 -I/usr/include/xmms2 -lnotify -lgdk_pixbuf-2.0 -lgio-2.0 -lgobject-2.0 -lglib-2.0

if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

echo "Failed to compile $i"

exit 1

fi

done

gcc src/*.o -o lxtask -lm -pthread -lnotify -lgdk_pixbuf-2.0 -lgio-2.0 -lgobject-2.0 -lglib-2.0 -lgtk-x11-2.0 -lgdk-x11-2.0 -lpangocairo-1.0 -latk-1.0 -lcairo -lpangoft2-1.0 -lpango-1.0 -lharfbuzz -lfontconfig -lfreetype -Wl,--export-dynamic -lgmodule-2.0 -lxmmsclient -lxmmsclient-glib -lstd

if [ $? -ne 0 ]; then

echo "Failed to link"

exit 1

fi

echo "Build successful"

Elf file

An Elf file, Executable and Linkable Format, according to IBM, “[…] is the standard binary format on operating systems such as Linux. Some of the capabilities of ELF are dynamic linking, dynamic loading, imposing run-time control on a program, and an improved method for creating shared libraries. The ELF representation of control data in an object file is platform-independent, which is an additional improvement over previous binary formats.” On its page on Wikipedia, it increases that “[…] is a common standard file format for executable files, object code, shared libraries, and core dumps”.

To check if the process has been successful, I’ve tried to execute the binary directly using:

./lxtask

Success! But now it’s time to implement something useful! Of course, it wasn’t a straight way. The real process was heavy-based on learning and reminding many things about C like compiling and linking process, tooling etc. Beyond that, it was necessary to copy the Rust standard lib to the appropriate directly to run the binary file.

Starting to work on LXTask

Normally, before beginning to work with a new code base, I try to use it to

understand its features and characteristics. I did the same here, looking for

strings that could help me find where I need to change for improving a phrase,

adding a new column or button, or inserting the bars I was willing.

Adding the bars was easy in some way; I just needed to find the code for the CPU and Memory bars, understand how it works superficially and replicate the same structure to the new ones.

After introducing some changes to the build.sh script, copying the Rust dynamic library to the right path to build successfully, I could finally see it working. The code changes were not so impressive, and that was not the goal. My challenge was trying to integrate the two languages in a usual feature, even if it was simple.

You can find the whole code on my GitHub fork of lxtask

In conclusion, this project was a valuable learning experience that pushed me to better understand both Rust and C, as well as the intricacies of integrating them. The successful integration of a Rust library into a C project demonstrated the potential for these two powerful languages to work together seamlessly. Moving forward, I am excited to continue exploring the possibilities of Rust in various projects and further refine my programming skills. If you are interested in seeing the complete code, feel free to visit my GitHub fork of LXTask.